In our last blog on knowledge transfer we mainly learned about the different types of knowledge transfer in companies and universities. Today we will focus on a very specific form of knowledge transfer, namely that of technology-related knowledge. And this is where technology transfer comes in.

With the end of the professor privilege in 2002, the scientific community has since been striving to transfer newly developed technologies into the economy in a targeted manner (BGBl I, p. 414). Whereas previously inventions were solely in the hands of university lecturers, it was also up to them to decide whether and, if so, how commercialization or transfer should take place. Statistical surveys have shown that approximately 70% of registered patents were attributable to companies and only 4% to university lecturers and researchers (study by EFI and Stifterverband for German Science, 2012). This was and still is due to the fact that transfer does not play a significant role at universities and that publications and the associated acquisition of third-party funding are much more important because they are rewarded by the existing system. Although transfer is referred to as the third pillar and is considered a central task of universities alongside research and teaching, this construct is not yet being put into practice.

As a consequnce, scientific results at universities are still primarily published as quickly as possible and are thus lost for possible patent applications because they are considered pre-publications. For this reason, technology transfer offices have been established at universities to address the problem more intensively.

But what are the tasks of a technology transfer office?

Classicly this includes:

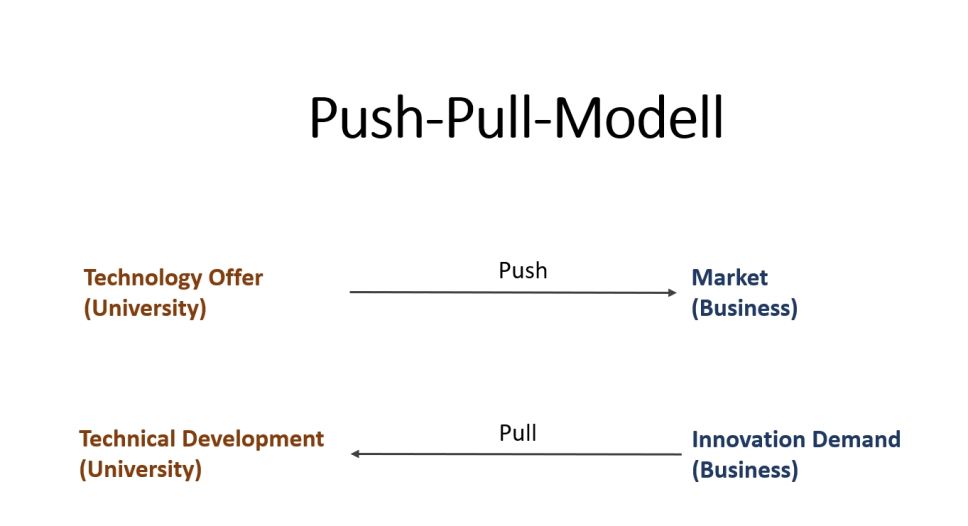

When it comes to technology transfer, there are initially two directions of orientation, whereby the push-pull model is applied here, because on the one hand we have inventions, technological achievements that are pushing their way onto the market (push), and on the other hand we have companies that are constantly looking for innovations and sometimes seek the support of universities (pull). Both supply and demand lead to transfer, only the orientation and the terms of the contract change.

In the “push” model, an offer of technology is first created which the developers believe has a market, and they then set out to find an economic partner who will provide them with market access. In the case of “pull,” there is a need for innovation, i.e., problems may have arisen that require a solution, or there may be a technological desire that needs to be fulfilled. Here, too, technological developments in universities or companies are in demand (see also Michael J.C. Martin's 1994 publication: Managing Innovation and Entrepreneurship in Technology-based Firms).

Figure 1: Orientation of Technology Transfer

When technology or knowledge is transferred within a company or organization, this is referred to as intra-organizational transfer. Examples of this include all events at a university where students and employees are taught knowledge in the form of lectures, seminars, colloquia, or internships.

Figure 2a: Intra-organisational Transfer: Results are transmitted internally, e.g., from the research department (A) to the administration (B).

When technology or knowledge is exchanged or transferred between similar organizations (e.g., universities), this usually takes place through personnel transfers, conferences, or mutual visits. This is referred to as interorganizational transfer.

Figure 2b: Inter-organisational Transfer: Results are transmitted from one organization to another.

In both cases, the technology and knowledge being shared is open, already published, or not protectable. In companies, it is common practice that new, unprotected knowledge or new technology is only disclosed between organizations once both sides have signed a confidentiality agreement in order to protect both the new technology and the disclosed knowledge internally. These are legally binding agreements such as a CDA (confidential disclosure agreement) or an NDA (non-disclosure agreement).

If the results are communicated directly from the research department to an interested party, user, or buyer, this is referred to as a direct transfer. In most cases, however, a transfer agency or a dedicated technology transfer office with the relevant negotiation expertise is likely to be involved, which is why this is referred to as an indirect transfer. This, in turn, can have both advantages and disadvantages.

There are two types of technology transfer:

Both are planned, time-limited processes supported by the private sector or the state and regulated by contract. Free technologies include patents and licenses, while goods-related technologies include special machines and complete factory facilities (Meyers Lexikon online).

As mentioned above, technology transfer has become established at universities alongside knowledge transfer and the spin-off scene. Strictly speaking, according to state higher education law, it is even one of the tasks of every university, along with research and teaching (LHG Baden-Württemberg §2 (5), 2005, version dated December 17, 2020). For technically oriented companies, technology transfer is part of the innovation process chain and should be anchored in every innovation strategy. Here is a brief insight into the tasks of technology transfer departments:

Validation, evaluation, and support of ideas and inventions

Every invention, every prototype, and every innovation started out as an idea. And these ideas must be nurtured and valued, because they are the driving force behind the future of every company and every research institution. In order to tap into the ideas of employees and researchers, those responsible can, for example, launch internal idea competitions, send out idea scouts, or set up idea consultation hours. These ideas must then be reviewed, evaluated, revised, shaped, and realigned before the rough diamonds can be turned into jewelry necklaces or technical prototypes. Since this process usually requires several iterations and does not always proceed smoothly, it is all the more important that the idea generators are well supported and advised.

Developing appropriate exploitation strategies for commercially interesting products and services

For every idea that leads to an exploitable product or service, a strategy tailored to the potential customer base must be prepared. In order to develop this strategy, it is necessary to be clear in advance about what you want to achieve with the developed product or new service. This involves defining the target market and researching the players. For your own product, it is important to determine its unique selling point (USP) and to create a list of arguments for the sales pitch.

Marketing of current, usable research results

In order to bring newly developed and immediately usable results to the relevant target audience, it is important to familiarize yourself with the most common marketing measures and use them in a targeted manner. Classic measures include social media channels, search engine optimization, email campaigns, mobile marketing, event marketing, press relations, and print mailings. When it comes to modern online media, it is particularly important to use company-specific platforms, but self-promotion on the homepage with downloadable short presentations should not be neglected either. Furthermore, information fairs have proven their worth, where technology transfer can present its results and engage in direct exchange with company representatives. And under no circumstances should tried-and-tested methods such as telephone calls and the distribution of print media be underestimated.

Initiation, negotiation, and conclusion of commercial exploitation, including selection of suitable licensees and cooperation partners

Once you have found suitable partners for offering your own results and you want to move beyond interested discussions to contract negotiations, it is advisable to agree on a letter of intent in addition to non-disclosure agreements (NDA or CDA). These can have the following names, among others:

In principle, all these declarations contain a description of the planned contract content and either a unilateral or bilateral declaration of intent to conclude a contract with the corresponding content. Such declarations may or may not be legally binding. Formulations relating to the content of the future contract and descriptions of the modalities of the planned negotiation process are often legally non-binding. These instruments do not constitute a preliminary contract and do not give rise to any claim to the conclusion of the planned contract. Despite their legal non-binding nature, they can be significant for the interpretation of the subsequent contract. However, legally binding provisions may also be included. These often relate to the event of negotiations being broken off. The distribution of costs is usually also regulated in a binding manner. The same applies to compliance with confidentiality obligations and, in some cases, to the mutual exclusivity of the negotiations (Adjuga.de).

In order to protect your own technical achievements from misuse by others, it is advisable to apply for a patent. Put simply, a patent allows you to use your own invention exclusively and prohibit others from doing so. This protects your investments and achievements from imitators and counterfeiters. If they nevertheless use the invention without the permission of the patent holder, this constitutes a patent infringement and can be prosecuted in court. Patents can be registered in different countries, and the inventions described in them are then also protected in those countries. Patents can also be sold, but this is not mandatory. This is because you can also earn money from them on an ongoing basis by “lending” rights of use for a fee. But more on that later.

Before an invention can be patented, several important steps must first be completed. The first step is to report the invention, e.g., to the in-house technology transfer department. This department first checks whether it makes sense to file a patent application with the German or European Patent Office, e.g., whether there has been any prior publication, whether a similar patent already exists, or whether the invention is perhaps not patentable at all. If all concerns can be dispelled, the invention disclosure is converted into a patent application, often with the active help and support of patent attorneys, and submitted to the relevant patent office. For some inventions that are intended to serve only the German market, and then only niche markets, it may well make sense for cost reasons to apply for a patent only in your own country. For other patents that have greater market potential, it is advisable to apply for a European patent right away, while in highly complex areas such as aerospace technology, the automotive industry, and biotechnology, applying for a global patent may be the right course of action.

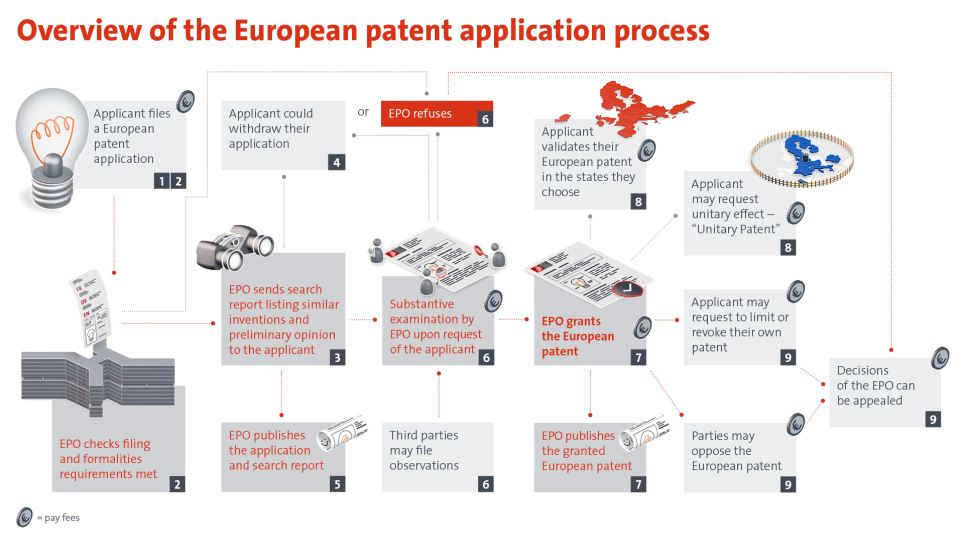

The following outlines the process for filing a patent application with the European Patent Office (EPO.org):

© EPO

After a patent application has been filed, e.g. with the European Patent Office (EPO), it is examined to determine whether the application and formal requirements have been met. If this is the case, the EPO prepares a search report listing similar inventions and asks the applicant for their opinion. If the patent application is not withdrawn, the EPO publishes the application together with the search report. The EPO then conducts a substantive examination. During this period, third parties may file objections to the patent application. If the objection is justified, the EPO may reject the application. However, if the examination is successful, the patent is granted and published. But the process is not over yet, because the inventor can now validate the patent in various selected countries or apply for a unitary patent with uniform effect. It is also important to note that third parties can file an opposition against the existing patent at any time, and the EPO must then make a decision, which can also be appealed. Many of these steps are subject to fees, and maintaining a patent also incurs fees that, like a good wine, increase steadily with age.

A patent therefore only makes sense if you want to use it to protect your own invention or exploit it. And in addition to selling patents, there is also the option of licensing them. But what exactly are licenses and how do you generate income from them?

According to legal-patent.com, the term licensing in the legal sense means transferring a positive right of use to a protected invention to a third party. And there are good reasons for doing so, here are three:

The decisive factors for the amount of the licenses are the freedoms or restrictions that are granted with the licensing and use of the rights:

In the case of simple licensing, the licensee is only permitted to use the invention and pays a license fee for this. The simple licensing model is very common in software use, for example.

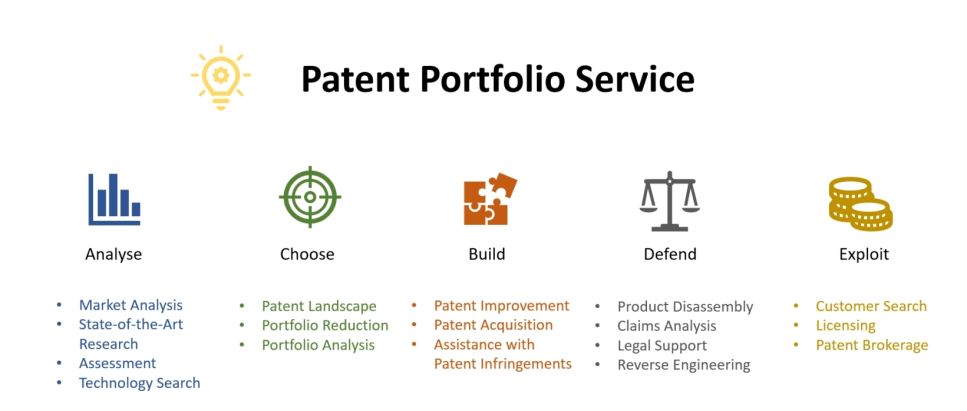

Figure 3: Tasks involved in managing the patent portfolio

The management of a patent portfolio involves various tasks, each of which deals with different “stages of maturity” of a patent or patent family. The first step in building a patent portfolio is analysis: What does the market say, what is the state of the art, how do I assess the prospects of success, and what comparable technologies are there? The next step is to gain an overview of the patent landscape, possibly dismantle existing portfolios, analyze new portfolios, and decide on a defensive or aggressive patent strategy when it comes to building a new portfolio. When building a patent portfolio, existing patents can be improved against attacks from competitors, and new related patents can be acquired to expand and strengthen the patent family. A broad, internationally registered patent portfolio helps to quickly identify patent circumvention and patent infringements and take action against them before competitors manage to establish a market with imitations. Existing patents are always vulnerable to attacks, whether through reverse engineering (replication through reverse development) and product disassembly, or patent infringement. Particularly in areas where high profits are generated and penalties for patent infringements are comparatively low, such as in the biotech and pharmaceutical industries, existing patents are subject to circumvention and, above all, non-compliance. In such cases, it is important to take countermeasures in good time and, even if legal proceedings are expensive and time-consuming, to initiate them immediately with the help of specialist law firms before the damage caused by the competition becomes immeasurable. Since patents, like fine wines and cheese, become more expensive after they are registered, it only makes sense to hold patents if they are financially viable, i.e., if they can be sold or licensed. Therefore, a thorough customer search must be conducted in a timely manner for each patented product.

Establishing a vital network of contacts in industry, associations, funding bodies, and decision-makers

Establishing a vital network of contacts in industry, associations, funding bodies, and decision-makers is essential for technology transfer work, because the existing patent portfolio not only needs to be maintained and organized, it also has to generate income.

![]()

© Rawpixel / Fotolia

The Dual-Use Issue

The dual-use issue describes the principle of technologies and goods being usable for both civilian and military purposes. The BAFA (Federal Office of Economics and Export Control) therefore points out that certain fields of knowledge and the associated expertise at universities may be relevant to export controls. The fields of knowledge affected include:

The following example of unintended technology and knowledge transfer shows how civilian research experiments can be misused for biological warfare:

Scientists in Australia conducted research into a reproductive inhibitor and modified a mousepox virus using genetic engineering methods. Although the experiment was successful, the modified virus was now resistant to known vaccines and proved to be lethal. After being published in a specialist journal, the research results were freely accessible on the internet and achieved significantly increased access figures in countries such as Russia, India, Pakistan, China, Iraq, and Iran (BAFA, Technology Transfer and Non-Proliferation, Guide for Industry and Science, May 2022). A primarily civilian use can probably be ruled out here.

Other examples include aluminum lipstick tubes, which can be repurposed as bullet casings (www.bex.ag), or the use of drones, sensor technology, and satellite technology (EU Parliament). Many goods and technologies are only identified as converted and repurposed components after a war and then find their way into the corresponding dual-use goods lists.

Espionage

In addition to technology transfer as a deliberate export, there is also the issue of unintentional technology transfer, which occurs in the context of increasingly frequent espionage activities and is accompanied by a criminal drain on innovation. Market-dominating technologies can fall into the hands of competitors through espionage activities in companies or universities, especially those of Chinese or American companies. The Friedrich-Alexander University (FAU) was the first German university to exclude all persons who were financed solely by the Chinese Scholarship Council (CSC) (Spiegel Panorama, July 29, 2023, 11:48 a.m.).

© Onidji / iStock

In September 2022, the German Federal Ministry of the Interior (BMI) warned of China's influence on German universities. The BMI views the cooperation between German universities and Confucius Institutes “extremely critically from a security perspective and regularly alerts universities to the associated dangers as part of its awareness-raising efforts” (Handelsblatt, 21 September 2022) .

Economic and research espionage, including unwanted technology leakage and the associated innovation deficit, cause enormous economic disadvantages for the target country, which is why the BAFA and its European counterparts regularly audit companies and, increasingly, universities with regard to export controls.

Knowledge is a valuable asset that must be protected within companies and transferred between established and new employees. Universities, in turn, transfer knowledge back to society. However, when knowledge is exchanged between universities and companies or between companies, it often involves the exploitation of intellectual property (IP) that has been incorporated into technological developments, for example. Technology transfer plays an important role here because this institution has the knowledge to exploit and protect this knowledge, for example in the form of patenting and licensing. Protecting knowledge gives a company a technological edge over its competitors, and a state that promotes a large number of companies that introduce many innovations can thereby ensure prosperity for society. This makes it all the more important for universities to protect themselves against unwanted knowledge leakage and for companies to prevent industrial espionage.

The University of Tübingen also has a technology transfer office, whose staff will be happy to provide you with information and advice on all aspects of this topic:

Technology Transfer Office at the University of Tübingen

https://uni-tuebingen.de/de/333